For many mariners, propulsion options haven’t changed much in the last century: you either use an inboard engine connected to a propellor shaft, or an outboard engine mounted on the rear. Both come with some considerable trade-offs, writes James Edwards, Marine Chief Engineer at Helix.

- For an outboard, the trade-off is the deck space sacrificed to accommodate the engine itself – often some of the most valuable ‘real estate’ of a vessel. That, along with the noise produced by the engine while in operation and the high centre of gravity.

- For an inboard, the trade-off is the compartment space sacrificed to accommodate engine rooms and prop shafts. Along with the space itself, you also need to handle new challenges around interior ventilation, fuel lines, and hot exhaust.

However, recent technological advances are providing us with an alternative option – a new generation of electric pod drives.

Azimuth thrusters into pod drives

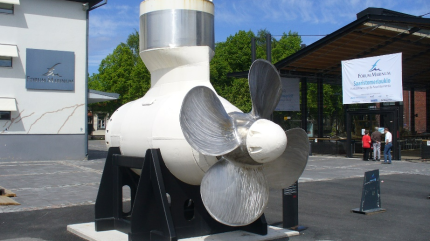

Pod drives are a type of azimuth thruster, a drive system which places the propeller underneath a ship and allows it to rotate along a vertical axis. These allow the propeller to always apply force in the direction needed – eliminating the need for rudders and significantly improving fuel economy. And, unlike the outboard motors, azimuth thrusters don’t need to take up space on-deck.

However, while azimuth thrusters don’t need to take up space on-deck, they are still restricted in placement: they either need their engine situated right above the propeller in an ‘l-drive’ configuration or are connected through a propshaft and ‘z-drive’.

Electric pod drives iterate on the azimuth thruster concept by building an electric motor directly into the submerged “pod” attached to the propeller, with the motor powered via an in-hull battery or generator. This is because, unlike an engine, an electric motor doesn’t need a constant flow of oxygen to function – only an electrical connection.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAs a result, the electric pod drive eliminates the need for the l-drive or z-drive and the space they typically require, all while delivering the benefits of an azimuth thruster. Additionally, since an electric motor doesn’t need to idle like an engine, electric pod drives also offer significant gains in fuel economy and reductions in maintenance burden.

The constraints of pods

Since hitting the market, pod drives have proven widely successful. However, they have always come with a significant snag: relatively high drag. This has hindered the ability to use pod drives for longer-range applications and for smaller vessels.

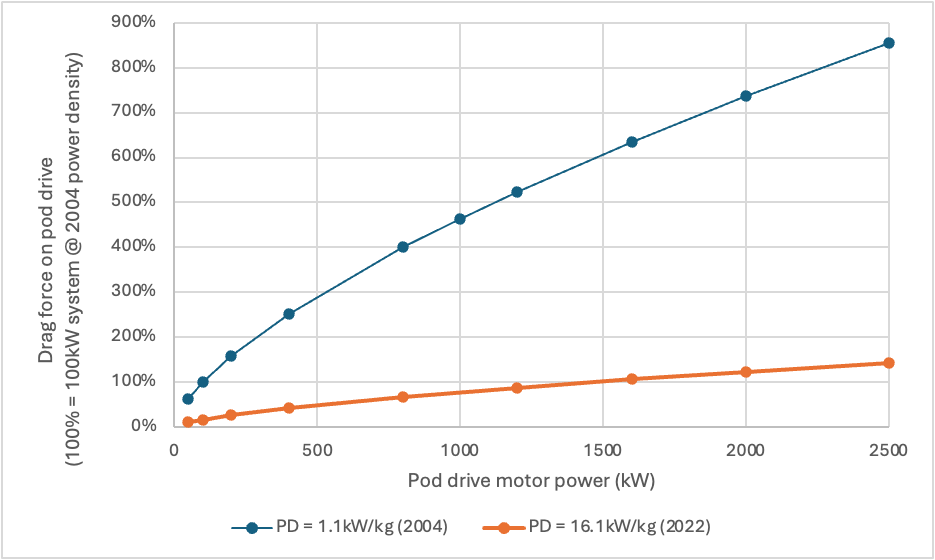

Because a pod drive is submerged, it creates drag in proportion to its cross-sectional area. In turn, the cross-sectional area of the pod is determined by the power of its motor.

To understand the consequences of this, we can take one of the more powerful motors that reached mass production just a couple of decades ago: the motor of the 2004 Toyota Prius. That achieved a power density – power output per unit of mass – of 1.1kW per kilogramme. So, if you wanted 100kW of power, you’d need 90.9kg of Prius motor. If we imagine this 100kW Prius motor is all-iron and shaped like a cube, its cross-sectional area would be around 500 square centimetres.

That generates a substantial amount of drag force, and in practice it nullifies most of the efficiencies and fuel economy benefits offered by a pod drive for a vessel of this size. And this is even more pronounced for smaller vessels – a 50kW motor of this power density would produce 63% as much drag for 50% of the power.

However, motor power is subject to the square-cube law: the cross-sectional area the motor presents for drag scales with the square of the motor’s diameter, but its total power scales with the cube.

That is, as a motor’s power rises, the relative amount lost to drag begins to drop off. A 1,000kW motor at Prius-levels of power density, for example, would experience 4.6x the drag of a 100kW unit for ten times the power. A 2,000kW motor would produce 7.4x the drag for 20x the power. As a result, this means that the motor power density is what determines the range and viable size for ships that use pods.

A marine killer app

As EV, battery, and motor technology has evolved in recent years, motor power densities have dramatically improved. As these motors inevitably migrate from cars to marine pod drive systems, this means that suddenly the range and viable size windows of ships using pod drives can widen dramatically.

Take the motor from the 2022 Lucid Air, for instance. Where the 2004 Prius had a power density of just 1.1kW per kilo, the 2022 Lucid motor could output 16.1kW per kilo. That same 100kW motor that once weighed 90.9kg now weighs just 3.1kg and has a cross-sectional area of 85 square centimetres – just 17% that of the 100kW Prius motor.

In software, there’s the idea of a ‘killer app’ – the application on your system that nobody else can offer. Think IBM in the 1980s with spreadsheets or Nintendo with Mario in the 1990s. Pod thrusters stand to be electrification’s killer app for marine: a propulsion architecture that dramatically changes how you plan and structure a vessel, eliminating noise and vibration while offering major gains in fuel economy and range.

Until recently, it was a killer app restricted due to these power density issues. Now however, we can finally realise the advantages of pod drives: both for larger ships that run into range limits with existing pods, and for small-to-mid sized marine applications. And this means, owing to these motor power density gains, pods are presenting marine with an opportunity to reexamine many of the propulsion trade-offs we’ve taken for granted for so many years.