Fresh off its Innovation Award win in the 2025 Ship Technology Excellence Awards, SecureLoad Systems lays out a clear diagnosis of why cargo operations still lag other parts of shipping’s digital transformation.

In this interview, CEO Nikhil Mathew and CTO Binoy Pilakkat explain how fragmented tools and ship–shore handoffs can undermine even “approved” plans at the execution stage, why a single engineering truth across vessel and office is becoming essential, and how SecureLoad is being shaped by high-complexity heavy-lift and offshore deployments. They also discuss the practical realities of adoption: reducing change anxiety, maintaining class-grade validation discipline, and scaling from specialized projects into bulk shipping without losing engineering depth.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Ship Technology (ST): What does winning the Innovation Award in Loading & Stability mean for SecureLoad Systems, and how does it align with the vision you set when you founded the company?

Nikhil: Winning the Innovation Award is a strong validation of the vision that originally drove SecureLoad. From the beginning, our belief was that loading and stability software should move beyond isolated, desktop-era tools and become connected, ship–shore infrastructure that actively supports modern cargo operations.

When we first started working on cargo-operation solutions, many experienced voices in the industry advised us against it. The general perception was that the market was small, operators were comfortable with existing tools, and loading computers were seen primarily as compliance-driven systems rather than areas for innovation. To some extent, that view reflected the reality of the time, if something worked and met class requirements, there was little pressure to change it.

However, we saw a clear gap. Cargo operations were becoming more complex, data was increasingly fragmented between ship and shore, and teams were repeating the same work across disconnected tools. We believed that loading and stability could be transformed into a collaborative, optimized, and transparent workflow rather than a last-minute verification exercise.

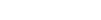

It took nearly five years of focused development to reach a solution that truly stood apart, one that delivers all the capabilities of a traditional loading computer while extending far beyond it with 3D interaction, optimization logic, and real-time ship–shore connectivity. The response we are now receiving from the market has been encouraging. What surprised us most was not resistance, but openness, once operators see that a system can genuinely simplify workflows and reduce operational friction, the mindset shifts from “why change?” to “why not?”

This award reinforces our belief that the industry is ready for practical, engineering-led innovation in cargo operations. It tells us that SecureLoad is addressing a real need and that the direction we chose, even when it seemed risky, aligns with where maritime operations are heading.

ST: Binoy, you’ve described cargo operations as a digital laggard compared with other parts of shipping. In practical terms, where do you still see the biggest gaps in how loading and stability are managed today?

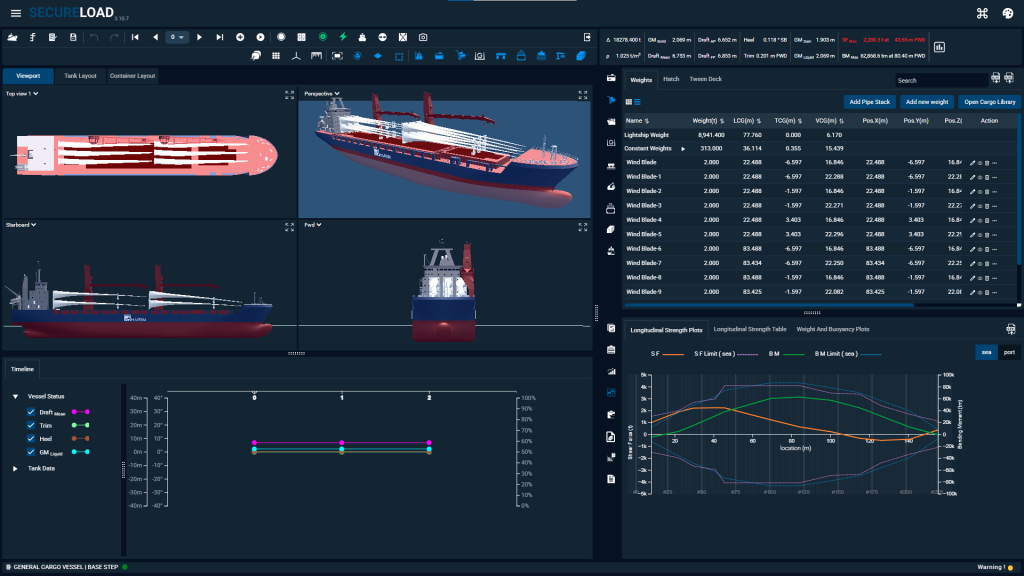

Binoy: The biggest gaps are still fragmented data, manual re-entry across multiple tools, and the absence of real-time ship–shore continuity in how loading and stability decisions are made. Cargo operations remain one of the few critical parts of shipping where planning, verification, and execution are still handled in disconnected silos.

If we look at a typical bulk cargo lifecycle, the challenge becomes very clear. A cargo inquiry usually reaches the chartering or commercial team first. At that stage, there is often no practical way to verify quickly and accurately, whether a specific vessel can load the cargo while complying with stability and longitudinal strength limits. Decisions are frequently based on rough indicators such as tonnes per centimeter or experience. The cargo details are then sent to the vessel, calculations are done onboard when crew availability permits, and a proper loading proposal is sent back. Because of time zones, workload, and back-and-forth communication, this process can easily take one to two days, delaying commercial decisions that ideally should be made within hours.

In breakbulk and project cargo, the engineering challenge is even more pronounced. Operators typically have strong engineering teams, but the workflow itself is fragmented. A stowage plan is created in one tool, passed manually to a hydrostatic solver for stability and strength checks, then recreated again in separate tools for accelerations, lashing design, and sometimes structural assessment. Each step requires manual transfer of centers of gravity, load cases, and assumptions, increasing the risk of inconsistency.

The most critical breakdown happens at execution. Even when an engineering department produces a thoroughly analyzed and approved loading plan, often reviewed by marine warranty surveyors, there is usually no direct way to transfer that approved condition into the onboard loading computer. The plan exists as reports and drawings, not as an executable loading condition. As a result, crews are forced to recreate the condition onboard based on interpretation and experience, sometimes introducing assumptions that can deviate materially from the engineered solution. In effect, a well-designed plan loses its value because it cannot be faithfully executed.

Across cargo segments, the common issue is the same: cargo operations lack a connected system that carries one approved model from planning, through verification, to execution. Given that cargo operations are among the highest-risk and highest-value activities in shipping, this disconnect remains one of the industry’s most significant digital gaps.

ST: SecureLoad grew out of your team’s naval architecture and cargo engineering background. Was there a particular incident or pattern in your earlier work that made you say, “We need to build something different”?

Nikhil: Yes, it wasn’t a single moment so much as a repeating pattern across many projects, but there were a few experiences that made the gap impossible to ignore.

In our early engineering work, we were involved in several urgent cargo and load-out projects, including one for a major EPC contractor. From a pure engineering perspective, the calculations themselves were not unusually complex. What stood out was how inefficient the process was. We were constantly switching between hydrostatics software, Excel spreadsheets, AutoCAD drawings, and manual checks, repeating the same steps repeatedly because the tools could not talk to each other. Even small changes meant redoing large parts of the workflow. At that point, it became clear that the problem was not engineering complexity, but the lack of an integrated system. Unfortunately, that is still how many operations are handled today.

At the same time, we were directly involved in live cargo operations, and one particular load-in/load-out operation left a lasting impression. During the operation, four crew members were physically positioned at the four corners of the vessel, manually reading drafts. One of us was in the wheelhouse coordinating ballast adjustments, while another engineer relayed draft readings over a walkie-talkie to the project manager standing near the cargo. The project manager had no real-time visibility of the vessel’s loading condition while the cargo was being placed, despite this being a high-value, high-risk operation.

What struck us was that this was happening in the project cargo segment, often considered the “business class” of cargo operations, with highly experienced teams and significant engineering effort behind every move. Yet, execution still relied heavily on manual communication and fragmented information simply because there was no technology that connected planning, calculations, and real-time execution.

That combination of repetitive engineering workflows onshore and limited visibility during execution onboard made the gap very clear. We realised that cargo operations did not need more reports or standalone tools; they needed a connected system that carries one engineering-approved model from planning, through verification, to execution. That realization is what ultimately led us to start building SecureLoad.

ST: When you talk to shipowners, how do you position SecureLoad—primarily as a next-generation loading computer, as a broader cargo operations platform, or something in between?

Nikhil: We don’t force a single positioning on every customer. Instead, SecureLoad scales with how the shipowner operates.

For pure asset owners who lease vessels to charterers, SecureLoad is positioned as a next-generation loading computer, ensuring compliance with class and statutory requirements using modern, web-based technology.

For shipowners who also operate their vessels, SecureLoad naturally evolves into a cargo operations platform. It allows them to plan, simulate, and manage cargo operations consistently across their fleet, reducing reliance on fragmented tools like Excel, standalone hydrostatics software, and manual checks.

We’ve observed that smaller fleets may initially only need a loading computer, but as fleet size and operational complexity increase, SecureLoad delivers the most value by centralizing cargo planning, reducing manual effort, and improving operational consistency across vessels.

ST: Many organizations already rely on legacy loadicators, spreadsheets, and bespoke tools. What have you found to be the most effective way to help them transition to a unified, browser-based system without overwhelming crews and office teams?

Binoy: Many organizations already rely on legacy loadicators, spreadsheets, and bespoke tools, so the key for us is to reduce change anxiety rather than force transformation.

We start by changing the surface, not the substance. SecureLoad mirrors existing workflows, terminology, and planning logic in a browser-based environment, so on day one it feels familiar. We migrate ship models, cargo libraries, and planning templates so teams are not rebuilding what already works; they are simply running it in one unified system.

From there, we phase capabilities instead of switching everything on at once. Typically, organizations start with the core cargo planning flow, then move to stability and longitudinal-strength verification during planning, and later adopt computed ballast, trim optimization, and step-by-step operational sequencing. Operationally, we often recommend running a few voyages in parallel (legacy tools alongside SecureLoad) so confidence builds without putting schedules or safety at risk. Training is short and task-based, and we actively close the feedback loop early to remove friction quickly.

We’ve also seen this play out clearly through our onboarding and trial experience. Users coming from long-established, table-driven workflows tend to find 2D views and structured data screens more intuitive, and we make sure those experiences are fully supported and not treated as secondary. At the same time, newer engineers and younger crew members naturally gravitate toward the 3D vessel view, finding it easier to visualize tank layouts, cargo placement, and operational constraints, with a much smaller learning curve.

Instead of forcing one way of working, SecureLoad deliberately supports both 2D and 3D interaction models. This allows experienced crews and office teams to transition calmly without disruption, while enabling newer users to adopt the platform almost immediately.

In short, our approach is simple: mirror what’s familiar, migrate what matters, phase what’s new, and support multiple ways of working. That’s how we move organizations to a unified, browser-based system without overwhelming crews or operations teams.

ST: A core promise of SecureLoad is a single source of truth across ship and shore. What have been the key challenges in making that work reliably at fleet scale?

Nikhil: The key challenge was building an ecosystem where a mandatory onboard deployment and a cloud-based system work together as one, with data syncing reliably between them. Vessel operations cannot depend purely on the cloud, yet they also cannot live in isolated onboard systems. Making these two environments behave as a single system was essential.

On top of that, we deliberately chose a web-based architecture, which introduced its own challenges. Unlike traditional desktop loading computers, computation happens on central servers while visualization and interaction take place in a browser on a different machine. Delivering a responsive, desktop-like experience, especially with full 3D interaction, required extensive optimization and custom development.

This was not a one-time effort. We had to continuously adapt to evolving web technologies, optimize performance, and refine data handling so that ship and shore teams could work on the same approved vessel model. Feedback from early adopters played a crucial role in shaping this system and validating that the approach works in real operational conditions.

The result is a centralized vessel model that supports multiple users across ship and shore, enabling a true single source of truth at fleet scale.

ST: Looking at projects on vessels such as Rotra Futura, Rotra Horizon, and OBANA, what real-world operational lessons have had the biggest impact on how SecureLoad has evolved?

Binoy: Working on vessels such as Rotra Futura, Rotra Horizon, and OBANA has been formative for SecureLoad because these are not standard ships operating with standard cargoes. In many cases, there was simply nothing comparable available in the market, which meant we could not rely on predefined templates or assumptions. We had to build and customize capabilities from the ground up to support their real operational needs.

From an engineering standpoint, these projects pushed us to handle new ship structure elements, unconventional load sequences, and highly specific operational constraints. While this work delivered immediate value to those vessels, it also accelerated our learning curve significantly. Each project exposed new edge cases that challenged traditional loading workflows and forced us to think beyond “tools” and towards end-to-end operational solutions.

Operationally, one of the biggest lessons was that cargo operations especially in breakbulk, heavy lift, and jack-up segments, cannot be fully standardized. Every operation introduces unique variables, and software must be flexible enough to support engineers and crews rather than forcing them into rigid workflows. This reinforced our focus on configurability, transparency, and engineering-led logic within SecureLoad.

Ultimately, projects like these shaped SecureLoad into a platform that evolves through real-world use. Each vessel and operation contributes to how the system improves, helping us stay aligned with how the industry works rather than how it looks on paper.

ST: How have 3D cargo modeling, step-based workflows, and ballast optimization changed the way your customers think about risk, responsibility, and sign-off in complex cargo operations?

Binoy: Together, these capabilities shift cargo operations from experience-driven, ad-hoc decision-making to transparent, auditable practice.

3D visualization and step-based workflows fundamentally changed how risk is understood. Humans naturally reason better when they can see geometry, clearances, and spatial relationships. When cargo, vessel structure, and constraints are visible in a shared 3D environment, potential hazards surface much earlier and in context. Crews and office teams no longer rely solely on interpretation of numbers or drawings, they can clearly see load paths and clearances, while the system continuously runs stability and longitudinal strength checks in the background. That significantly reduces guesswork and focuses attention on the true limits of the operation.

Ballast optimization completes this shift by removing much of the subjectivity traditionally involved in ballast planning. Historically, engineers and crews would manually adjust tanks incrementally, often stopping at a “good enough” solution to avoid reworking the entire plan. Optimization algorithms allow the system to explore the full solution space under real constraints and propose ballast distributions that may not be immediately intuitive but are objectively better. This frees engineers and crews from repetitive trial-and-error work and allows them to focus on higher-level questions like commercial flexibility, operational robustness, and safety margins.

Importantly, this does not remove responsibility from experienced professionals. Instead, it changes how they think. Decisions are no longer driven by gut feeling alone but supported by visible geometry, mathematical optimization, and a shared model that everyone can trust. The outcome is clearer accountability, fewer subjective compromises, and approvals that stand up to scrutiny.

ST: SecureLoad connects chartering, operations, engineering, and vessel crews in one environment. What internal changes do you encourage your customers to make to really unlock that cross-functional collaboration?

Nikhil: The biggest change we encourage is a mindset shift, not a technical one.

From a technology perspective, access is no longer the barrier. SecureLoad is web-based, available wherever there is connectivity, and designed so that chartering, operations, engineering, and vessel teams can all see the same information. The real challenge is moving away from the traditional habit of working in isolation and only sharing information at the very end of the process.

In many industries, people are comfortable signing up, exploring a tool, and learning by doing. In shipping, change is often approached more cautiously. New technology is sometimes resisted not because it is difficult to use, but simply because it represents a change in established workflows. Unlocking collaboration starts when teams are willing to involve others earlier allowing chartering to see technical constraints, engineering to understand commercial drivers, and crews to see the intent behind a loading plan.

That said, collaboration only works when there is discipline around how data is created and shared. A single environment does not automatically mean clarity. We encourage customers to establish simple internal rules: define who owns vessel data, ensure inputs are complete and accurate, and document assumptions clearly. If information is entered inconsistently or without context, even the best collaborative system becomes hard to use.

When teams adopt both elements, openness to shared workflows and basic governance around data, cross-functional collaboration starts to happen naturally. The result is fewer late-stage surprises, better-aligned decisions, and a shared understanding of why a particular loading plan or operational choice was made.

ST: Integration is a strong theme in your platform ballast control, tank sensors, CAD, and more. What principles guide your decision on which integrations are strategic for SecureLoad?

Binoy: Our guiding principle is simple: integrations must remove friction and improve decision quality. We do not integrate systems for the sake of connectivity alone.

From the start, we prioritize integrations that eliminate duplicate data entry, strengthen confidence in the “live” ship model, and directly support safety-critical decisions during cargo operations. If an integration does not meaningfully reduce manual work or improve operational clarity, it is not considered strategic.

For SecureLoad, the most valuable integrations are those that help us understand two things: the state of the vessel and the state of the cargo operation relative to the plan. This can be sensor data from ballast systems or tank measurements, but it can just as well be data coming from another software or planning tool. What matters is whether that data helps crews and shore teams see what is happening and act on it with confidence.

Ultimately, our integration strategy is selective, and purpose driven. We focus on connections that make cargo operations clearer, safer, and more transparent, rather than trying to connect to everything and adding complexity without operational value.

ST: You’ve obtained approvals from several IACS class societies. Beyond compliance, how has working with class shaped your approach to validation, safety margins, and releasing new capabilities?

Binoy: Working closely with IACS class societies has had a lasting influence on how we design, validate, and release SecureLoad; not just from a compliance standpoint, but in how we think about operational reliability under real conditions.

One of the most important lessons has been the value of traceability and discipline in calculations. Class approval requires every result to be reproducible, auditable, and defensible. That reinforced a culture where safety margins, assumptions, and calculation logic must be explicit rather than implicit. It also pushed us to adopt rigorous regression testing before any new capability is released into production, ensuring that improvements never compromise existing, approved behavior.

From a product perspective, class rules, many of which are written based on hard-earned experience and worst-case scenarios, proved to be an invaluable design guide. In some cases, we initially built interfaces or workflows that looked elegant but did not fully support users under stress or time pressure. Class feedback helped us identify where additional checks, warnings, or constraints were not just regulatory requirements, but practical safeguards for real operations.

Another key impact has been on input validation and data quality. Class approval forced us to be very deliberate about how data is entered, validated, and constrained within the system. This means users can trust that the calculations are not only correct, but that the underlying inputs have passed a meaningful quality gate reducing the risk of silent errors propagating through the workflow.

Overall, working with class societies has effectively embedded decades of operational experience into the SecureLoad platform. It has shaped how we think about safety margins, how conservative we need to be in edge cases, and how carefully new features must be introduced. The result is a system that not only meets regulatory requirements but is better suited to the realities of high-pressure cargo operations.

ST: You chose to start with demanding segments like heavy lift, offshore, MPP carriers, and floating docks. Why begin there, and how do you see your market focus expanding over the next few years?

Nikhil: We deliberately started with heavy lift, offshore, MPP carriers, and floating docks because these segments stress every part of a loading and stability system. If a platform works reliably in environments where cargo is non-standard, operations are highly sequenced, and margins for error are small, it creates a strong foundation for everything that follows.

There was also a clear strategic reason. In most industries, early adopters drive the acceptance of new technology, and in shipping those early adopters tend to operate at the most complex end of the spectrum. Heavy-lift and offshore operators are compelled to use advanced tools simply to execute their work safely and competitively. Complexity leaves little room for outdated workflows, making these segments more open to meaningful innovation.

The challenge for us was that these operators did not want a lightweight MVP. They expected a complete, production-ready solution. As a result, what might normally be considered a “minimum viable product” for SecureLoad had to be a fully capable system from day one covering stability, longitudinal strength, ballast logic, sequencing, and operational workflows. While this significantly raised the technical bar, it also accelerated our learning and led to faster acceptance once the platform proved itself in real operations.

That early traction helped us build a portfolio of highly demanding vessels and a strong order book, which in turn created credibility beyond the early-adopter segment. As those reference projects matured, we naturally began expanding into adjacent markets.

We started with MPP and heavy-lift vessels, expanded into offshore units, and are now actively entering the dry bulk segment, where the underlying problems are simpler, but the operational scale is much larger. Wet bulk, from a mathematical and modelling perspective, is even more structured and opens the door to further optimization-driven use cases.

Over the next few years, our focus remains on bulk, breakbulk, and offshore segments, scaling SecureLoad from complex, one-off operations into broader fleet-wide adoption without compromising the engineering depth that defines the platform.

ST: When a new customer goes live with SecureLoad, where do you typically see the quickest, most visible impact on their operations?

Nikhil: The quickest and most visible impact is usually in planning time particularly around ballast calculations and lifting simulations. Customers see fewer plan iterations, faster turnaround on feasibility checks, and clearer communication between ship and shore because everyone is working from the same digital model.

Very early on, teams notice that tasks which previously involved manual trial-and-error such as adjusting ballast to meet draft and stability limits or validating lifting scenarios can now be completed quickly and consistently.

ST: Your roadmap includes Stowage Planner 3D, Acceleration & Lashing, and a Structural Digital Twin. Which of these near-term developments do you see as most transformative for your users, and why?

Binoy: In the near term, we see Stowage Planner 3D and Acceleration & Lashing as the most transformative additions to the SecureLoad platform, because together they complete the operational loop for unitized cargo planning.

Stowage Planner 3D allows users to move from abstract planning to a fully visual, geometry-driven workflow. For many users, this alone significantly shortens planning cycles and improves confidence before an operation even begins. Acceleration & Lashing builds directly on that foundation by addressing one of the most critical questions in cargo operations: whether the planned stowage can be safely executed and transported under real motion and load cases. By bringing acceleration analysis and cargo securing design into the same workflow, users can evaluate feasibility, safety, and compliance without breaking continuity or recreating models elsewhere.

Together, these capabilities extend SecureLoad from verification into end-to-end cargo operation planning, covering feasibility, safety, and execution in one environment. While they are designed first for maritime use, the underlying logic of geometry-based planning and load response is equally relevant across other transport modes such as rail, road, and multimodal logistics, opening broader applicability over time.

The Structural Digital Twin remains a powerful longer-term development, but in the near term, Stowage Planner 3D and Acceleration & Lashing will have the most immediate and visible impact on how users plan, validate, and deliver complex cargo operations.

ST: Looking three to five years ahead, how would you like shipowners and project cargo stakeholders to describe SecureLoad Systems’ role in the industry?

Nikhil: In three to five years, we want SecureLoad Systems to be seen as the trusted backbone for cargo planning and execution. A system stakeholders rely on to assess feasibility, manage risk, and execute cargo operations with confidence across ship and shore.

If operators can say that SecureLoad helped them make faster decisions, reduce uncertainty, and deliver safer, more predictable cargo operations, then we’ve done our job.

ST: Nikhil and Binoy, thank you for the candid discussion. Your points on execution risk—where approved plans can still be rebuilt onboard—and on ship–shore continuity as infrastructure, not a feature, were particularly insightful. We also appreciate the practical view on adoption and class-driven validation.